First published in “Phronesis in Pieces” newsletter at billschmitt.substack.com on Jan. 17, 2023

A recent study of empathy from Cambridge University prompted me to think about the role of that virtue in the pursuit of practical wisdom.

CNN’s report on this research focused on the finding that women around the world performed better than men on a standardized test of “cognitive empathy.” On average, the results held substantially true in 57 countries, independent of such factors as geography or cultural backgrounds.

My basic reaction was twofold: First, it was no surprise that women excel in empathy. Second, it was good news that thought leaders had encouraged, in some small way, discussing empathy at our tables of moral deliberation in a world of relativism and polarization.

My next reaction was to inquire further into how science defines empathy as a positive force. Might this discussion yield something more than a headline about male-female differences?

I like to think of compassion, or empathy, as part of the checklist for modern-day explorations of “phronesis,” a quality Aristotle discussed in his Nicomachean Ethics. He called it a kind of wisdom—I would say it’s virtuous wisdom—which gathers insightful knowledge and applies it to practical judgments and decisions enhancing the common good and true happiness. Going beyond scientific knowledge, I see this as common sense informed by Judeo-Christian values.

Please think of my values-added approach to phronesis as “Aristotle Plus.” Of course, this renowned pre-Christian Greek hardly needs a premium channel, but I avidly hunt for content which fits comfortably with practical thinking while also resonating with my Catholic roots.

You might call the compassionate, open-minded component of phronesis “a muse you can use”—a kind of evangelization that Catholics should make part of their programming. These days, the Church can offer helpful reminders about God to people who seem to struggle without Him. An embrace of both faith and reason will enable our secularized culture to tackle its urgent challenges in other-centered, problem-solving ways.

By my lights, empathetic people are inclined toward genuine “encounters” with others. Pope Francis uses this term when he calls for Catholics—and all people of good will—to venture beyond the church doors, to reach out and listen, especially to the marginalized.

Instead of trampling on the inherent dignity of those without a strong voice in the public square, we must strive to know and appreciate the unique experiences and aspirations of all, so they become part of our common-good calculus.

Because I equate empathy with compassionate caring, I also think of another pope. John Paul II spoke of key gifts—receptivity, sensitivity, generosity, and maternity—that we must bring to others if we are to answer a mandate issued by the Second Vatican Council—“to aid humanity in not falling.”

It’s no coincidence that John Paul saw these gifts as central to “the feminine genius,” which he discussed in a 1988 apostolic letter, On the Dignity and Vocation of Women.

A “Catholic Answers” commentator wrote in 2005 that “the Church has called women to be the stealth weapon of the twenty-first century” because they bring those gifts to people whose spectrum of suffering echoes in today’s society.

This point invites criticism from many people who would charge that Catholicism precludes other ways in which women could bless the world, such as ordination to the priesthood. I ask that we set aside that debate for purposes of this discussion, just as we downplay the journalists’ focus on a male-female empathy contest.

I believe all people, in our diversity, should contribute our best traits to the overarching goal of keeping humanity from falling. And I return to my question: What is this thing called empathy, and how can we use it?

It turns out that the Cambridge scholars were not measuring the characteristic as I simplistically defined it.

CNN explained that the article in the multidisciplinary journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences looked at “cognitive empathy” as an intellectual viewpoint toward interactions and relationships. This entails individuals’ ability “to understand what someone else might be thinking or feeling, and they are even able to use that knowledge to predict how the person will act or feel going forward.”

Say a person tells you he or she had an uncomfortable family reunion during the holidays. Using cognitive empathy, “you understand how that bad time makes the person feel.” Once you put yourself in that person’s shoes, you “are even able to use that knowledge to predict how the person will act or feel going forward.”

This is different from “affective empathy,” or “emotional empathy,” the connection made when you feel another person’s emotions and respond with your own appropriate emotion. That’s the definition I had assumed.

Say a person is crying about a broken relationship, so you “feel sad too, and feel compassion for that person,” as CNN put it.

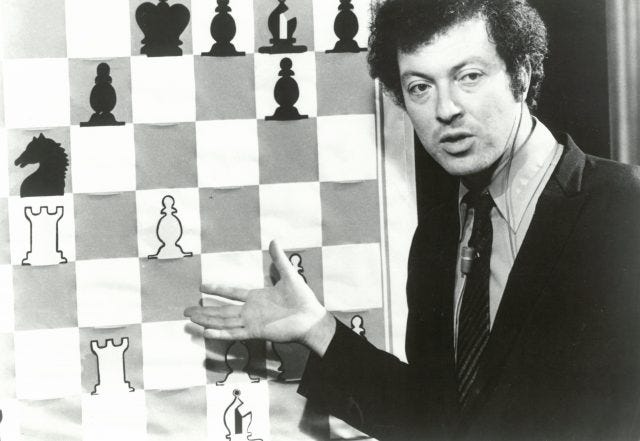

The Cambridge researchers have posted questionnaires that test for both forms of empathy. But, for their new findings, they used the “Eyes Test” to explore the cognition, or “theory of mind” that kicked in. They showed participants photos of different people—actually, only of the area around a person’s eyes, forming a facial expression. For each face card, the researchers asked what the person was thinking or feeling.

Their key finding seems to be that more than 300,000 participants, spanning the globe, performed this analysis, and the pattern of their answers showed that this “cognitive empathy” was largely independent of such factors as local culture, and even age and language.

As with most studies, the scientists’ key determination was that this finding reveals the need for more research. For example, we might probe the social or biological reasons why women outpace men on the empathic path.

I am always in favor of asking more questions. I also acknowledge that I might be missing or misinterpreting the full potential of this study. But, reluctantly accepting the empathy definition provided, I return to my curiosity about empathy as a virtue that contributes to wise engagement.

It sounds like the cognitive version is relevant to phronesis because it is indeed practical. If one can analyze facial expressions or statements and thus walk “in another person’s shoes,” and then can predict how that person might feel or act in the future, this might help devise an action, or intervention. That could be virtuous insofar as it benefits the person and achieves broader goals.

In comparison, affective or emotional empathy sounds like a mere feeling of compassion that should be an easy assumption among those at tables of deliberation in the public square.

So cognitive empathy is empowering, and emotional empathy is an endearing background feature? I offer several cautionary notes. First, I wonder if there are really two empathies, or rather one tool to be wielded and one quality to be nurtured. Second, I wonder if men and women wield the tool differently. Third, I wonder if any kind of empathy can be measured using facial expressions.

The researchers spotlighted here, setting the rules for the version they studied, were focused on the person perceiving rather than the person perceived. In this cognitive mode, we speak of the other, but we risk minimizing the other as a face in the crowd, or worse, as essentially a lab animal to be assessed and acted upon accordingly.

Only the perceiver is empowered, and the power has a flimsy justification, based on a shallow interaction and unverified judgment.

Can a “theory of mind” toward which we gravitate in one-on-one situations be generalized to yield problem-solving steps affecting a community or the common good? This open-ended claim to understand people may be the train of thought at Cambridge College in Boston, which offers an “empathy certificate.” It may be the dubious goal of some folks studying social psychology.

With all due respect, I hope we can minimize control games, where we extend our supposed predictive powers beyond one person’s facial expression to a whole category of actors or potential actions. This oversimplifies complex human inclinations.

Cognitive and psychological methods to interpret and label people appeal to today’s advocates and influencers as influential tools. Our society loves to group individuals together into opposing (rather than collaborating) camps in order to create talking points which polarize.

For example, problem-solvers might ask us to change the nickname of a pandemic because it can make some people violent. The Hill gave this warning in a September 2020 article: “The use of the phrase ‘China virus’ by top administration officials , including President Trump, has coincided with a surge in discrimination against Asian-Americans, according to a new study.”

Likewise, for the sake of peace and order, decision-makers may want to censor the free marketplace of ideas, blocking information that disagrees with authoritative sources; we might easily suspect a malevolent intent behind comments which otherwise would increase knowledge—and deserve First Amendment protection.

There are certainly situations in which the virtue of prudence does warrant devising precautionary limitations for the common good, based on our instincts about, and our concern for, the volatile chemistry of people and circumstances.

But overall, I prefer the adoption of emotional empathy—a habit of compassion fed by sharing, and learning from, experiences with people in their diversity and dignity—as the fundamental aid in pursuing wisdom. Both leaders and followers can and should share this habit, creating a common ground for truly interactive conversations.

Some may argue that compassion is a given in public discussions based on equity, diversity, and inclusion; mere “emotion” adds no efficacy when we are solving problems. Not so fast! We often catch leaders and followers alike forgetting empathy in their calculus. This sensibility is indispensable but elusive, particularly when a crisis inclines us toward quick fixes, snap judgments, groupthink, exercising power, or saving face. In such cases, the quality of mercy is strained.

Let’s keep the sense of mystery when we play the “empathy” card from the phronesis deck of virtues. Amid today’s frayed solidarity, we should scrutinize our assertions that we “understand” human aspirations, relationships, and dignity. Some things, such as the complicated interplay among people, and between souls and their God, are beyond our understanding. Compassion centered on hearts, not on minds, is a humbling wisdom we can promote in Church evangelization.

Affective empathy syncs up the souls of the governing and the governed. It empowers people on common ground. It expands our perceptions and allows transformative encounters. It elevates everyone’s sensitivity, receptivity, generosity, and maternity.

The report from Cambridge University decided that empathy—at least one kind of it—knows no boundaries. We think we can read a person like a book. But we also need to love people as stories which are incomplete, interactive, and dynamically hopeful.

Those scientists determined cognition through face cards. That is not the whole story. An empathy card belongs in everyone’s deck of wisdom, but how we choose and use it at the table of deliberation, pursuing win-win situations, will display our virtue.