First published in “Phronesis in Pieces” at billschmitt.substack.com on Dec. 19, 2022.

The world of political reporting groans with a desperate need for graduates of the Shelby Lyman School of Journalism.

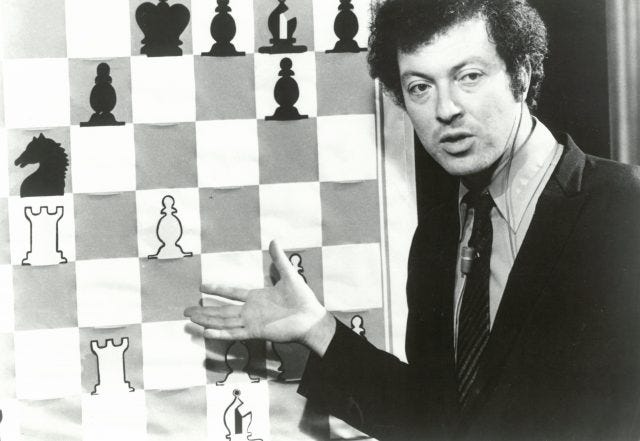

This is a problem because there is no Shelby Lyman School of Journalism, and most people don’t remember its namesake. Lyman did exist (1936–2019), but he never practiced journalism per se.

He did write a popular chess column that appeared in dozens of newspapers for years. And, most famously, he was the TV anchorman, you might say, covering what The New York Times has called “one of the most ballyhooed competitive events of the 1970s, a Cold War confrontation in Reykjavik, Iceland, between the two most brilliant chess players in the world.”

Lyman volunteered during the summer of 1972 to host a pioneering endeavor—live coverage for PBS stations of the World Chess Championship match between Brooklyn native Bobby Fischer and Soviet grandmaster Boris Spassky.

Some of the combatants’ 21 games consumed copious time, but Lyman did not tire. Fans called for more, so coverage of the rounds (which were riddled with controversy) was even allowed to pre-empt Sesame Street.

An informal New York Post survey of bars in the city revealed that most of them had their single TV tuned to PBS’s slow-paced sport, according to a blog at chess.com. The coverage drew the highest ratings of any show that had appeared on the young public network. At some points, an estimated 2 million viewers were said to be tuned in.

Lyman broadcast the series of programs from a bare-bones studio near his upstate New York home. A 35-year-old Harvard grad with no media experience, he invested TV time in the regimen which chess experts like him typically adopted at other high-level matches—namely, back-and-forth banter about how the game was going and what the moves meant.

He sparked detailed, esoteric, but oddly appealing dialogues with a few chess-club champions seated around him. He shifted cardboard chess pieces on a demonstration board whenever a bell rang to announce that Fischer or Spassky had made the latest move. This news was phoned in from spectators in Iceland.

While he carefully updated one board to show the current state of play, Lyman could walk over to a separate “analysis” board, where he and his panel of commentators could critique moves and visualize options or opportunities. They discussed the likely gambits the players were forging in light of all 64 squares as a connected whole.

Participants’ differing insights, looking backward and forward, sounded like this: Fischer was “setting up a couple of threats,” or “he was justified in moving that pawn.” Spassky’s queen was “being harassed” by major and minor pieces, or he initiated the “Schliemann defense.” You can pick up the lingo by watching these videos of “Chess Chat” and a follow-up Lyman broadcast in 1984.

I was a rising high school sophomore in 1972, with no training in journalism yet and little exposure to the art of play-by-play sports coverage, except for some Mets games. But I found the “color commentary”—and the “suspense” of waiting ten minutes or more for the next move—downright addictive.

The experience nurtured my zeal for a kind of “Washington bureau” vocation that seems old-fashioned to many. I never mastered the model, but I admired its focus on rigorous curiosity and enlightened dialogue, alongside the necessary dedication to solid research, deadline reliability, and well-crafted writing.

Extra qualities of this ethos include: patient but proactive waiting for a federal government that was designed for a deliberative pace; responding to “breaks in the action” by asking questions of knowledgeable sources; sharing varied visions of the possibilities ahead; and trying to read the minds of newsmakers without grasping for instant headlines or jumping to narrative-based judgments.

I do not question other forms of journalism, practiced by professionals with different approaches. But I like to think uncomplicated, inquisitive engagement at the intersection of knowable facts and human nature constitutes the ethos—or the curriculum—of the Shelby Lyman School.

Today’s coverage of national policy-making would benefit from a larger cadre of political reporters who are allowed and able to take time, to piece together a spectrum of details, and help their audiences see a big picture containing clues for fresh, constructive ideas.

Don’t assume that such journalists would be bland geeks, lacking strong opinions or the ability to build and inspire an audience. Back when I finally did study journalism, at Fordham, I recall discovering I.F. Stone (1907-1989) as an admirable variation of the Lyman paradigm.

His newsletter about Washington, I.F. Stone’s Weekly, became influential through its simple perspicacity—his willingness to delve into transcripts and government documents that revealed what people in power actually said and thought.

Communicating the fruits of his phronesis, his virtuous pursuit of wisdom in service to the common good, he became a progressive thought-leader who helped to advance such causes as civil rights.

Whatever causes and values formed the whole of Lyman’s good life, one of his goals was to promote a game he saw as a source of meaning and happiness. He is quoted as saying:

“Chess is a dramatic event. You could hear the swords clang on the shields with every move. They went at each other. The average person is turned onto chess when it’s presented right. Trying to figure out the next move is a fascinating adventure—an adventure people can get into.”

I have one more reason for promoting a “school” that exists only in my imaginative metaverse: You might say that all participants in the political arena and the public square need to be fans of chess, or at least of its thought patterns.

In these days when serious societal concerns are viewed through lenses of entertainment, persuasion, and gamesmanship, you might say we often must choose between two models of play—the good order of chess or the demeaning chaos of Rollerball.

There are plenty of smart, powerful leaders playing their “long game” of strategy regarding particular issues—or broad goals on a global scale. They hold a full complement of castles, knights, and bishops, and they naturally aim to control the “whole board.” While they are preoccupied with their high-stakes chess matches, they benefit when we are distracted by the bursts of sound and fury, the dopamine hits of bread and circuses, the rules of manipulation and confusion, which were portrayed in Rollerball, a classic 1975 film.

The latter arena generates play-by-play announcements from the loudest voices and biggest egos, armed with the most compelling statistics (or clickbait), grabbing and wasting the sporadic attention of hyped-up crowds.

The former arena is the quieter, more personal, more nuanced setting where an informed public enjoys taking a serious thing seriously. We are waiting and watching for each successive move, encouraged to think and converse about individuals’ gambits and incremental steps toward victory. Who is doing what, to what end, in what context, with what implications?

Our announcer for this “Game of Kings” coverage, applicable to politics, should be some future Shelby Lyman. Not weighty in the world’s eyes, but still the show’s anchor, he or she will help us all to become better analysts—and, eventually, better players in contests where the world needs champions.

Image from ClipSafari, an online collection of Creative Commons designs. Photo of Shelby Lyman from the U.S Chess Federation.