Our society’s embrace of the all-purpose polarizer—the worldview labeled “oppressed vs. oppressor” or “victim vs. victimizer”—prompts us to weaponize everything, including guilt. We’ve got lots of glass houses and plenty of stones.

Guilt is already a formidable material when it resides inside us. Today’s politicized viewpoints, seen in campus protest mobs and many other settings, reveal that our personal pangs are now marauding throughout a secular culture that has no cure for them.

Where No Analogy Has Gone Before

Such pangs are nothing new, in the present or future. They were pictured in “The Doomsday Machine,” a familiar episode of the original Star Trek. It was televised in the 1960s, when Americans were hyper-aware of the nuclear threat called mutual assured destruction (MAD).

In the story, a massive planet-eating device was loose in the galaxy, having been invented by a civilization to destroy an enemy’s planet and then having turned against its creators. This liberated it to feed on solar systems as its Golden Corral buffet.

The plot thickened, with a touch of Moby Dick. The machine nearly wrecked Commodore Matt Decker’s starship. And he was traumatized by guilt over an error in judgment which, amid the mayhem, killed his crew of four hundred.

In his pain, he commandeered Captain James Kirk’s USS Enterprise to undertake a hopeless attack on the device. He then stole a shuttle craft, piloting it down the machine’s long maw. He perished, but the planet-killer was unscathed. Ultimately, free of Decker’s obsessive influence, Kirk & Co. proceeded to destroy the menace.

We’ll leave outer space on a galvanizing note. Early in the episode, Decker described with horror his automated nemesis: “They say there’s no devil, Jim, but there is! Right out of hell. I saw it.”

This story connects to 2024 via thoughts about the devil and the nature of guilt.

The Plot is Still Thickening

An article in Catholic Answers magazine, “Satan Wants You to Feel Bad,”reminds us that we derive the name Satan from the Hebrew for “accuser.” Author John Grondelski says he notices “two kinds of accusation people encounter when they examine their consciences and prepare for confession.”

The first type is the private work of a well-formed, active conscience. It makes us feel guilty, either before or after a moral mistake. We speak of examining our conscience although, in a sense, it examines us.

Its purpose is not to haunt or persecute a person, or to trigger thoughts of doom, but to engage our moral accountability, calling us to seek and receive forgiveness. This is God’s gift to reboot us—to help us get right with Him and our neighbors, for our good and a greater good, Grondelski says.

Type-two guilt comes from Satan—as an end, not a means. It deflates our dignity, inflicting depression and despair. There’s real danger here: Persons in this state, if they find no relief, may normalize and externalize the condition. Paraphrasing the movie Wall Street, “guilt is good.”

We grapple with this force, possibly seeking internal respite by dismissing its importance or numbing it by artificial means. Meanwhile, we risk opening the door for broader mischief and chaos. Results may vary, but we are well advised to steer clear of manipulative accusations, regardless of ideology.

Christ gave us the Church in order to deal with (not to dwell upon) the problem of sin—including both kinds of guilt. When individuals and communities build Godly relationships, love, justice, and mercy douse the fire. Otherwise, the flames spread.

America’s affliction with depression and suicide gives us reason to be concerned. Psychologists both explore this problem and offer therapies. Their research extends into analyses of clinical depression as opposed to guilt, shame, and “self-hate,” but all of these are precarious.

One Psychology Today article addresses “self-hate” by recommending a process of “self-forgiveness” which we initiate by forgiving others. This is good advice, although laypersons could question whether it’s possible. True forgiveness is an act of love, and as the maxim goes, “You can’t give to others what you don’t have yourself.”

Without transcendent, personal values, a populace forgetting God might be tempted to minimize type-one guilt and maximize utilitarian, externalized guilt.

The Young and the Innocent

Social commentator Rob Henderson, known for his 2024 book, Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class, coined the term “luxury beliefs” several years ago, defining them as “ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class but often inflict real costs on the lower classes.”

This would explain some progressive approaches by which elites choose certain practices—deemed prestigious, like luxury goods—while they might display only shallow sympathy for lower classes’ options. Henderson says positions such as defunding the police, emphasizing identity politics, and dismissing traditional family strengths can be signals used uncaringly by elites as a kind of currency among themselves.

In an “amen” not mentioned by Henderson, a new South Park episode, “The End of Obesity,” satirizes “fat kid” Cartman’s inability to afford one of the new weight-loss drugs. The doctor’s alternative prescription is to watch Lizzo videos and feel good about himself. Cartman interprets: “Rich people get Ozempic, poor people get body positivity.”

Luxury beliefs help diagnose the odd inclusiveness/separatism mash-up now evolving on college campuses. But Henderson does not seem to explore an underlying motivation—namely, the guilt that some students may wrestle with regarding their wealth and their admission to the “best” schools. They know there’s an awful imbalance of class and clout in the US economy and the world.

An Inside Higher Education article by Steven Mintz affirms this. When students arrive at the most competitive colleges, “many feel enormously guilty and struggle to rectify their lottery win.”

Faced with embarrassment about privilege, on or off campus, it seems many people of all ages and backgrounds cultivate belief in the “oppressed vs. oppressor” model. This might include calls for DEI and ESG standards, as well as various policies and practices affecting social cohesion.

Some of their proposals are idealistically simple or pragmatically soothing, amenable to an “auto-pilot” mode sustained by metrics, policy reforms, appearance, and performance. Innovative virtue systems leapfrog over the rigors and renewal of an active conscience. They may make sense for one situation or issue, but not fit so well in another.

They’re often cordoned off from debate and quality assessment, even though they affect complicated human circumstances—from life paths and freedoms to emotions and self-esteem.

Most people take anti-oppression stands with the best intentions. But the self-protective fervor with which some advocates condemn anyone who questions the remedies creates division. An oppressive spirit flows from guilt and imposes guilt on others.

Our Built-In Virtue System

Another human circumstance we should respect is the hunger for truth and practical wisdom. We generally want to do the right and just thing, and we need solid truths, however inconvenient, as a common ground for reasoning and reckoning.

When informed consciences justly accuse us of abandoning the mistreated and marginalized, we should wise up. But we may bristle if we suspect that word games and psy-ops of a post-truth culture are trying to change facts or blur nuances. Perceived manipulation accordingly spreads a type-two guilt that disturbs our efforts to use reason and faith.

“Conscience expresses itself in acts of judgment which reflect the truth about the good, and not in arbitrary decisions,” according to the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church. There is no “universal” conscience to conform to. It’s part of each life’s adventure.

Exercising the conscience, ideally but not necessarily in light of the nation’s most enduring principles, requires diligent discernment by each individual, not groupthink delivered by theories and opinion leaders.

Mature judgments, giving each person responsibility and agency, must be based on “an insistent search for truth … allowing oneself to be guided by that truth in one’s actions,” according to the Compendium (paragraph 139).

In other words, the currency of conscience is unadulterated reality, not mere ideas we can adopt to gain advantage, prestige, or a fake peace of mind. A single currency allows us to exchange wisdom.

Thinking about guilt is complicated, so human beings try to avoid it. “The modern drama of guilt has not followed the script that was written for it,” historian Wilfred McClay said in a 2018 lecture to the deNicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame.

The philosopher Nietzsche expected a further development of mankind that would remove the desire for a judgmental God, spawn the smart but solitary Ubermensch, and set us free from guilt.

Instead, technology has made us more likely to know about, care about, and try to control much of the world around us. Confronting a scene of immense change and connectedness, “the range of our moral responsibility and potential guilt” has expanded, said McClay. In fact, “guilt has metastasized.”

Guilt by Disassociation

Therapeutic approaches have tried to paint guilt as merely psychological, subjective, and emotional. Many view forgiveness as merely a genteel act, rather than the sharing of a gift to preserve and unite our human ecology.

In some circles, reconciliation (or the lack of it) may be a way of saying “nothing really matters.” Elsewhere, it matters greatly.

America may be in the grip of a particular paradox, as McClay put it: We face “a world of limitless moralism rooted in limitless relativism.” Plenty of people, all along the political spectrum, define their own truths about good and evil and target recalcitrants who disagree.

We then point fingers of guilt at individuals and entire groups without understanding their whole story or motivation. Our accusations assume the worst about people’s hearts. We become hateful, blithely calling others cruel names, even promoting violence.

Alas, we forget that fingers can be pointed back toward us. Nobody’s perfect. (This suggests caution in using “elites” as a negative moniker, for example.)

The social problems which cause our angry guilt never get solved. In fact, many cases involve both sides sharing responsibility, as with America’s unsustainable debt. Politicians barely address important issues if neither party foresees a victory through blame.

The modern MADs of mutual assured detraction and distraction paralyze us. The conscientious power of type-one guilt—to nudge us toward correcting moral errors and reconnecting with others—isn’t allowed to kick in.

If only we recognized that we all share responsibility for this mess, we could recover common purpose and common sense.

We need someone to resurrect awareness of guilt as both a potential doomsday machine and a difficult but desirable path away from the precipice. Our contentious marketplace of ideas and infotainment too rarely serves up wisdom that seeps into individual souls.

Can We Handle the Truth?

Faith is the only force that can shift us toward a more peaceful, humble road—traveled by comrades in meaningful relationships, not by advocacy groups rallying the troops.

Yes, religion got a bad reputation as a punitive, destructive force when it was the primary institution talking about guilt. This recalls Archbishop Fulton Sheen’s remark from decades ago: “There are not one hundred people in the US who hate the Catholic Church, but there are millions who hate what they wrongly perceive the Catholic Church to be.”

Of course, this applies to views of other religions, too, such as current warnings about “Christian nationalists” and vile stereotypes of peoples and beliefs. And, yes, some Catholic leaders and followers made grave mistakes trying to be managers of guilt, especially when the Church held both spiritual and earthly reins.

Today, in a culture that has a God-shaped hole in its heart, secular strategists try to seize the reins of guilt everywhere, inflicting it on foes and absolving it for friends. Modern-day indulgences?

Toying with personal conscience can sever connections not only with God and neighbor, but with our own integrity and trustworthy participation in civic life. In all of these realms, good, evil, and compassion really matter.

Religious leaders need to start talking about guilt again—not pointing fingers, but opening their arms to everyone who feels the pangs. That’s just about everyone, although some of us give the devil the reins before we regain self-control.

Shall we reconcile with others before we forgive ourselves? Well, it’s easier first to receive love and then extend that love to our least favorite politicians.

Believers need to spread more stories about their quests traversing sin, reckoning, guilt, confession, redemption, and hope. If we listen closely to news interviews, we’ll hear ex-victims, and ex-victimizers, voice thanks for their life-changing journeys all the time.

Step one is easy: Recall the hymn, “Amazing Grace.” When guilt is weaponized and conscience seems doomed, it’s time to announce the good news of our neediness—and our empowerment.

This worldview can begin to disarm all protagonists and sow seeds of peaceful penitence: “’Twas grace that taught my heart to fear, and grace my fears relieved.”

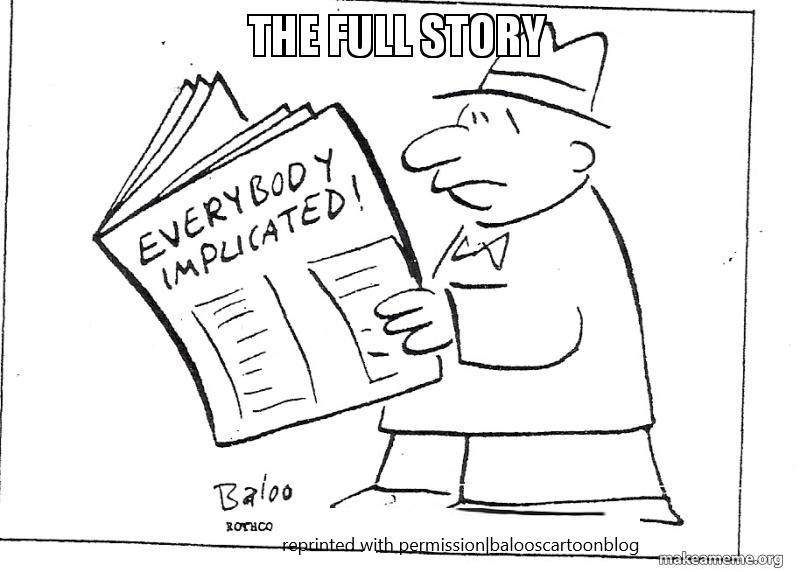

First image generated by the AI Designer function of Microsoft’s Bing. Second image, reprinted by permission, is from the cartoonist Rex May, known as “Baloo.” See his website.